Work Text:

During his years on the force, Officer Tom Jenks had seen many far more gruesome sights than the Bonfire Butcher. There were car crashes and house fires, gangland shootings between kids young enough to be Boy Scouts, beatings and brutality and freak household accidents. But at the end of his career, it was the face of the Bonfire Butcher that would come back to him in his nightmares.

It was perhaps the surreal dreamlike quality of the day itself that locked that moment into his psyche. It was a beautiful day. The first call to come in was a vague report of a medical emergency with massive blood loss. (The caller had hung up without clarifying.) An ambulance had been dispatched first and Officer Jenks who was late for his lunch break had followed unenthusiastically as a courtesy just to see if he could help. He was already on his way when the next two calls came in, each reporting that a "crazy-ass sonovabitch"—or as the second caller had more delicately phrased it, "this weird creepy guy"—had set fire to something in the parking lot of the same address.

The ambulance pulled in just ahead of him and with the instincts of paramedics, the EMTs headed straight for the man covered in blood. With the instincts of a cop, Jenks called for backup before he even got the car into park. Jumping from the car, he pulled his gun with one hand and motioned for the EMT to halt with the other. "Whoa, there!"

The Bonfire Butcher was poking at the fire with a cast iron rod—no not a rod, tongs. He was adjusting the bits of wood and crumpled up newspaper and dismembered human gore with a pair of fireplace tongs with his left hand and casually drinking out of a bottle in his right. The EMT froze just a few paces away, perhaps finally noticing that the bloody man had no apparent wounds. The Butcher followed the police officer's gaze and glanced over his shoulder at the paramedics. He lazily waved his bottle behind him at an open door. "He's in room twelve." The paramedics were slow to move so he waved the sloshing bottle at the open door again. "There. He's in there."

"He?" Jenks prompted. When he'd been younger, he would have come in screaming, "Get down! Get down! Drop it!" When his backup rolled up in a few minutes, that's probably exactly what they'd be screaming with a few extra "motherfuckers" thrown in for good measure. But Jenks knew there was a voice you used for jaded career criminals and a voice you used for scared punk kids (generally the most dangerous, because kids were stupid) and there was the voice you used on crazy-ass sons of bitches and Jenks had to agree with that caller. This one had crazy-ass written all over him. As calmly as he could manage and not once loosening his grip on his gun, he repeated, "He?"

"Well," the Butcher giggled, "most of him." He poked at the fire again and nudged a chunk of burning wood closer to the toes that had thus far escaped the fire.

Procedure told Jenks that he shouldn't let the suspect burn evidence. But, hell, from where he stood they had evidence to spare. The Butcher wiped sweat off his face with the back of his hand (the one with the bottle) and left behind bloody streaks on his forehead and right cheek. Evidence to spare. Jenks had his eyes on the Butcher's hand (the one with those cast iron tongs) and decided to see how far he could get with the talking-softly-to-the-nice-crazy-man approach before the cavalry arrived. "How are ya doing?" he asked.

The Bonfire Butcher seemed mildly confused, but after only a brief hesitation he answered, "I'm good. You?"

"Fine, fine," Jenks answered. Rookies never believed this worked. Provided he didn't end up with his skull smashed open, face down in that fire, he was going to have a hell of a story to tell them. "Quiet day—until a few minutes ago. I was just going to grab a sandwich, but it can wait."

"Ah." The man with blood matting his hair seemed genuinely apologetic. "Sorry about that. Do you want a drink?"

He offered Jenks the bottle and Jenks tried not to wince. The Butcher seemed to notice for the first time that he might have some hygiene issues and he tried, comically in vain, to find a clean bit of shirt to wipe the mouth of the bottle off on. That was when Jenks realized the man was wearing hospital scrubs.

"Can you tell me exactly what's going on here?" Jenks asked.

The Butcher looked at him, looked back at the fire, looked at him. He tilted his head to one side and smiled sheepishly and said, "Nice day for a barbecue?"

It was meant to be a statement, but it came out a question. Jenks had seen that smile before. It was the smile of a guy who'd been pulled over for doing 110 in a 55 mile per hour zone and asked, "Was I going over the limit, officer?" It was the smile that said, "Look, you and I both know that I'm completely fucked here, but could you just be a pal? Huh?" It was not the smile you expected to see on a guy poking flaming body parts in the parking lot of a cheap motel. Crazy-ass sonovabitch was an understatement.

"You seem like a nice guy," Jenks told the Butcher. And the surreal part was that he really did. "Could you just do me a little favor?"

The Butcher took a swig from his bottle and waited expectantly.

"It's not for me that I'm asking really. It's just that I called for backup when I arrived on the scene. Nothing against you, mind you, just protocol. And, well, we've had a lot of the old guys retiring lately, which means we've got a lot of rookies on the force. And you know how these kids are. Hot heads, think they know everything."

The Butcher rolled his eyes and nodded knowingly. Good, Jenks had guessed his age range correctly. He continued, "So any minute now, they're all gonna come flying in here, itching for something to shoot and...they see that much blood and they might panic. And you know, reckless discharge of a firearm can just ruin a rookie's career. Look, I know they're annoying little piss ants, but for the sake of the dumb kids, would you be willing to put down the thing that just might be mistaken for a weapon before the little shits get here?"

The Bonfire Butcher would achieve urban legend status and strike terror in the hearts of many a slumber party and scout camp meeting for generations to come. In several incarnations, it was said he had a chainsaw where his right hand should be. In the campfire versions, he was often roasting hotdogs that turned out to be fingers or something more ribald. He would live on in the collective psyche as a figure of malevolence and horror.

On this beautiful spring day, in the flesh, the Bonfire Butcher seemed to exist in a state of perpetual befuddlement. He took in Jenks' words and looked down at the tongs in one hand and the bottle in the other, seemingly unclear on which of them he was being asked to put down. He took one last swig and tossed the bottle into the fire.

Jenks tried to count that as progress. "Lovely. Now if you could just put those down as well." He looked pointedly at the long cast iron fireplace tongs.

The Butcher poked at the fire again, clearly intent on evenly distributing the flames around the sizzling gore. "You won't let them put the fire out until it's completely burned, will you?" The Bonfire Butcher looked at Officer Jenks with the pitiful eyes of a child. "It's important that it burns up completely. It's—it's bad. It's just bad and it has to burn. It's hard to explain."

"Okay." Jenks didn't know what else to say to that.

"Did you ever see that movie about that guy whose hand got cut off and it came to life again and..."

Jenks had seen three or four different horror movies that might fit that description. The fire popped and muscles seemed to twitch in the flames. For a horrible second, Jenks thought he saw a hand trying to crawl out. "There aren't any hands in there, are there?"

"What?" the Butcher seemed startled. "No, no, nothing superior to the head of the femur."

"Oh, good." Jenks wasn't sure what they were talking about any longer, but he could hear sirens so, one way or the other, this was going to be over soon. "That'll be the rookies arriving. If you could just put that down?"

The Bonfire Butcher nodded and obediently put the iron tongs on the ground at his feet. He then casually walked over to the edge of the parking lot and sat on the railing next to the motel stairs where he waited patiently as the backup squad cars squealed into the parking lot.

Jenks then did something he would regret for the rest of his life. Instead of walking around the smoke and fire, he followed the Butcher along a straight line downwind. The scent hit him and his stomach growled. "God, I really could go for barbecue."

*

The evening before the Bonfire Butcher was arrested, night mechanic Mike Stanley placed a curse on every school bus driver ever born. It had no effect. School bus drivers are immune to fresh curses on account of already being cursed with being school bus drivers. But it made Stanley feel a little better anyway.

He glared at the work order again. "Acting funny." That was it. That was the whole damned work order. Bus #27 was "acting funny."

He'd told them before. He told them all the damned time. All the mechanics agreed. His supervisor had written a memo and it wasn't often you got the supervisor to write a memo. And still the damned drivers submitted work orders marked with useless crap like, "acting funny."

How do you fix "acting funny"? Did they perhaps not notice that the buses they drove were somewhat on the large side? Large and full of thousands of moving parts? Was that a subtle thing people had trouble noticing? Was he being unreasonable to expect them to at least hint at what part of the bus they thought might need servicing? Were the brakes squealing? The engine chugging?

He wasn't asking them to be mechanics. He didn't expect to receive work orders that said, "Clean the third cylinder and replace the fan belt." Mildred submitted work orders that said things like, "Demons from hell have opened a portal to our dimension somewhere under the hood and every time I go uphill they all do the cha-cha-cha." And the mechanics were all perfectly happy with that. You at least had a place to start with something doing the cha-cha-cha under the hood when you go uphill.

"Acting funny" gave you no place to start at all. With the full agreement of all the mechanics and a memo from his supervisor to back him up, Stanley did not have to put up with this crap. Almost against his will his feet took him to bus #27. Glowering, he climbed into the driver's seat. If it starts, I'm done, he thought. I'll just note on the work order that it started fine and if they still want it serviced, they'll need to be more specific.

It started.

Good. There. It works. I'm done. But now that he was on the bus, he glanced in the rear view mirror. The rear view that showed him nothing of the road and only the rows of empty seats, empty seats that tomorrow would be filled with a bunch of noisy, screaming, snot-nosed kids. He shifted the bus into gear and made another deal with himself. As long as the brakes work, I'm done. If it starts and the brakes work, you've got a functioning bus. Congratulations. He pulled the bus forward and then slammed on the brakes.

The brakes worked.

Good. There. It works. I'm done. And then some traitorous voice in the very back of his mind added, just once around the lot and I park it back where I started and then I'm done.

On the first turn, something felt loose. He felt like he was over-steering to make a simple 90-degree turn. It felt funny. Okay, damn it, he'd give them "funny" but couldn't the driver have written "steering acting funny." Stanley was still annoyed when he hit the last turn and the bus just didn't. He was so startled that he didn't brake fast enough and he hit the corrugated metal fence. It was neither the first nor last time that the fence had been so abused and Stanley figured the supervisor probably wouldn't even notice the fresh dent.

But he cursed all the bus drivers of the world one more time anyway.

*

It was a slow news day the afternoon the Bonfire Butcher was arrested. The butterflies on the other side of the world fluttered their wings in just the right way and there were no freak tornadoes on the east coast. Somewhere in Hollywood a starlet was popping pills and chugging booze, but today was not the day it would catch up with her. Not a single school bus in all of New Jersey crashed into anything that day (and not one person ever thanked Mike Stanley).

There was little chance under any circumstances that a dismemberment—with an arson chaser—would have been reported with restraint. And the Dr. Jekyll jokes were inevitable as soon as the Butcher's identity was public. But if it hadn't been such a slow news day, the alliterative nickname wouldn't have been in the first headlines. As gruesome as it was, it likely would have been reported with less dramatic phrases alongside the gang shootings and car crashes, cobbled together from the AP news feed and the police blotter and possibly other "sources" (which Paul Henderson suspected mostly meant "tweets" these days).

Henderson watched from CJ's Bar. After the sun went down, CJ's became a real bar, but now before the dinner crowd had even arrived, CJ's was a quiet little restaurant with a cheap and tasty taco salad. And until the dinner crowd did start to fill the place, no one cared if he spread out his papers and took up a table for hours. He had an office. He just liked it better at CJ's, except for the TV over the bar, which he normally found to be a distraction. He would put in his earbuds and pretend to listen to music and ignore it, but today was a slow news day, which meant the TV crews had literally nothing better to do than cover a bizarre arrest outside a local motel. And even jaded Paul Henderson couldn't resist a good media circus flickering over the bar.

The TV people were already at the police station broadcasting live when the Bonfire Butcher was pulled from the back of the police car in handcuffs. His scrubs were solid red at gut level—there was even a large stain on his back and Henderson couldn't guess how that had happened—but the drips and spatters at the edges were somehow more gruesome. The prosecution would bring in blood spatter experts who would point out that the vertical line of blood was from a slashed artery pulsing out of the victim. Worst of all were the smears on his face. The cops really should have let the poor schmuck wipe up his face before frog marching him in front of television crews. Psychopath or not, no one should have to face the media with blood on his face. This guy's poor lawyer was going to be totally fucked.

And then a reporter leaned in with a microphone. "Are you sorry for what you've done?" she asked.

The perp stopped. He turned and looked at the woman with the microphone. The cameraman shifted for a better angle on both of them. Henderson cringed. The cops were not supposed to let this sort of thing happen. The media did not get to grill handcuffed suspects on the police station steps.

"Are you sorry for what you've done?" the woman repeated.

The TV station updated the scroll just in time for a close-up of his response.

DR. JAMES WILSON, ONCOLOGIST, BONFIRE BUTCHER.

"Seriously?" Wilson blinked. "I should have done this years ago."

"His lawyer is totally fucked," Paul Henderson repeated out loud and his phone rang on cue.

*

When Dr. Lisa Cuddy was told what happened, she didn't seem surprised or shocked or even particularly disturbed.

"I'm sure there's just been a misunderstanding." She actually said that. Joe Carpenter underlined it in his notes to emphasize that he was not paraphrasing. She had actually said, "I'm sure there's just been a misunderstanding."

He had explained twice already, but he didn't seem to be getting through to the woman at all. Her polished public relations facade was wearing on his nerves at this point. "I tell you one of your staff hacked another to pieces and set fire to the spare bits. You call that a misunderstanding?"

She smiled awkwardly. "Well, I supposed if you put it like that it sounds... But I'm sure there's a perfectly rational... Sometimes Dr. House takes more medication than he should...."

Carpenter wondered if she was mixing up the perp and victim, but before he could correct her, she made it clear she had not.

"Look," she said bluntly. "Greg House has always been a complete bastard. I don't know what he did this time, but I'm sure he had it coming."

Dr. Cuddy waved him out of her office so she could phone a lawyer for the accused.

*

For his part, Greg House hadn't been shocked either. When Wilson grabbed him in a choke hold without warning and shoved a needle in his neck, his primary feeling was curiosity. He was mildly chagrined that he hadn't realized Wilson was up to something. There had to be a clue that he'd missed. Well, props to Wilson for getting the drop on him. It would be interesting to find out what Wilson had planned.

He was slightly embarrassed when the panic started to creep in. It was one thing to let Wilson catch him off guard. It was another to let him see fear. But Wilson was genuinely angry this time and the grip he had on his neck was fierce. It was just possible Wilson wasn't taking into account his own adrenaline surge increasing his normal strength. House's vision was closing in on the periphery and he was having trouble breathing, indicating that Wilson was compressing his carotid artery reducing blood flow to his brain while simultaneously pressing painfully against his windpipe. (That was going to be a nasty bruise in the morning.) And House wasn't sure what was in the hypodermic that even now was oozing into his veins and down to his heart.

It was the choke hold on his windpipe that was the worst. He could have remained calm, faked calm for Wilson's benefit at least, if it had just been the unknown sedative or the fluffy gray brain damage settling in from the compressed carotid. But the ability to breathe was something even a suicidal dick like Greg House couldn't suppress. He began to thrash and kick and he wasn't curious at all—well, barely at all, much—he just couldn't breathe. He clawed Wilson's arm, literally clawed, leaving a bloody row of gashes on his forearm and he felt bad about that for a flickering moment, but it wasn't his fault, damn it. Wilson had started this and he was not going to apologize for scratching Wilson's arm. He was not going to apologize for something that wasn't his fault.

Greg House never did apologize for scratching James Wilson's arm.

*

He had thought the hospital director was an especially cold-hearted bitch. Yet after Joe Carpenter left Dr. Cuddy's office, he talked to half the hospital staff (or so it felt) and only those who admitted they didn't actually know either man—not actually known as such, seen, heard of, but not really known to talk to—expressed even a fraction of the horror or revulsion he expected.

Only one person even asked if the victim had suffered.

And the glimmer in Dr. Eric Foreman's eyes when he asked had unsettled Carpenter more than Dr. Cuddy's ridiculous insistence that it was all a silly misunderstanding.

The District Attorney would probably want more interviews, but Carpenter was tempted to call it a day. The cops had already decided they knew all they needed to. They knew whodunit and they had that man locked up. Figuring out why wasn't their problem and, for that matter, the DA didn't have to prove motive either. It just played better for the jury if you had a story to tell them. They watched Law & Order and they expected a show if they had to do damned jury duty at a courthouse that didn't even validate for parking unless you parked in the far lot that only the lawyers knew about. The DA wouldn't be happy if he couldn't give him at least a first draft of a story idea. (And, "the bastard had it coming," was not the story the DA wanted to hear.)

A little man in a lab coat walked up to him, stopped a few feet away, smiled, started to open his mouth, seemed to think better of it, turned, and walked away. Before he turned the corner of the hallway, he stopped to looked back at Carpenter and he seemed about to speak again, but didn't and walked away again. Out of sight around the corner, Carpenter heard him giggle.

Carpenter was officially done for the day.

*

The first time Paul Henderson laid eyes on his client in the flesh, he was wearing a jailhouse orange outfit that bore an eerie resemblance to the blood soaked scrubs on the afternoon news. He made a mental note to petition for civilian duds for his court appearances.

Henderson tried to get a feel for the case, but all his client could say was, "I was just done. Just done. I'd tried everything else. Love, understanding, tough love, rejection, ultimatums, bribes, threats, begging, trickery, deceit, screaming, more begging. The only other option I had left would be to kill the guy." Wilson smiled wistfully. Eventually, he put his head down on the table and took a nap while Henderson stared into space and pondered his own options.

*

Gregory House floated among the clouds. His vital essence stretched beyond the confines of what he would normally think of as his body, flowing like a liquid one moment, swirling like mist the next. There was only one part of him that felt solid, felt real. His center, where his vortex of self spiraled, his bladder. It was heavy and tight and annoying and since they didn't seem to have urinals in the clouds and he wouldn't have known how to use one if they did, he just pissed into void. And then his soul was made of cotton candy again and it was lovely. He had never known such bliss. He did not believe in heaven, but the idea of nirvana sprang to mind then. Disconnected thoughts gradually drifted together and held hands.

Nirvana.

Love.

Shotgun.

If he got to hang out with Kurt Cobain because of this, Wilson was totally forgiven.

*

The Bonfire Butcher was booked through to jail along with a request from the District Attorney for a private cell. "That's nice," the receiving clerk said, "would he like some raspberry jam on top as well?" It wasn't an unusual request in gang cases where they wanted to make sure the inmate wasn't communicating with accomplices, but it just didn't apply here and it wasn't as if they had a surplus of vacancies.

Unlike most receiving clerks who would stuff an inmate into the first available cell, Officer Patricia Cho put a lot of thought into pairing compatible cell mates. She read a lot of psychology books, but most of the other officers figured it had more to do with her serving a year in Animal Control where she'd learned how to match up kennel mates for minimal hassle. You just didn't put the nervous biters in with the high-strung barkers. It was common sense.

Patricia Cho was not on duty when the Bonfire Butcher was arrested.

However, Officer Mitchell Adams also gave careful consideration to cell assignments and what was fair. It was just that Adams had a different idea of fair.

"Okay, how's this? The Bonfire Butcher versus Tank Foster."

"Unarmed?" Officer Martin asked.

"They searched him when they brought him in." It wasn't actually an affirmative, but at least ruled out the larger impossible-to-hide weapons.

"Okay, so no chainsaw," Martin agreed. This was how rumors sometimes happened. They didn't spread so much as spontaneously coalesce out of the ether. "Tank squashes him like a bug in fifteen."

The other officers nodded. Clear consensus so Adams moved on. "How about the Butcher versus one of the meth heads?"

"Butcher." Instant consensus.

"Two meth heads?"

"Butcher."

"Against two of them?"

"Those meth heads are made of toothpicks. Sending them in with the Bonfire Butcher will be like lambs to slaughter."

Slaughter. There was an idea. Adams pulled up the record to make sure he hadn't been transferred out yet. "Slaughter versus the Butcher."

"Slaughter," Martin said.

"Butcher," Smith countered.

"Bobby will wipe the floor with him."

"No-Shit-Slaughter is all bad ass with a gun or when he's punching a woman half his size, but unarmed against a psychopath?"

"Middle-aged psychopath."

"But psychopath. Psychopaths always have the edge," Smith insisted.

"Fifty on No-Shit," Martin offered.

"You're on," Smith said.

That was Adams' idea of fair. He typed the cell assignment into the computer log.

*

Bobby Slaughter was a repeat offender whose pedigree pre-dated their computer system. A very literal-minded transcriptionist had entered him exactly as the words had appeared on his first arrest report. "SLAUGHTER NO SHIT NOT AN ALIAS, BOBBY NOT ROBERT." The name had sort of stuck. There had at first been the general thought that someone should fix that one of these days, but no one considered themselves to be that someone and "one of these days" hadn't arrived.

There seemed to be an unspoken contest between the circuit court judges to see who was finally going to lose it in open court when The State of New Jersey vs Bobby Not Robert Slaughter No Shit Not An Alias landed on the docket. (His Honorable Gabriel Alvarez had racked up considerable points the last time Slaughter had faced charges of drug possession by addressing the accused as Mr. Slaughter No Shit Not An Alias twice without cracking a smile.)

Slaughter for his part had a sense of humor. He was six foot four, had washboard abs and arms like tree trunks. He could afford a sense of humor. No-Shit-Slaughter had a nice ring to it anyway. It added a lot of credibility to your threats when you could tell a man that even the judge called you that. "The name is Bobby (not Robert, Bobby, you got that?) Slaughter and everybody knows that Bobby Slaughter does not mess around. You can even ask the police. They will tell you that the one thing you can count on is that Slaughter is telling you the truth. No shit."

Within an hour of the Bonfire Butcher being placed in his cell, No-Shit-Slaughter confessed to all the charges against him as well as two other crimes they had suspected him of but were lacking evidence, a carjacking he had an alibi for, a gas station hold-up where security footage showed a robber who was a full foot shorter than Bobby, and a jewel heist that Officer Jack Linden had completely fabricated just to make sure he was clear on what was going on.

"Can we keep the first three confessions?" Officer Fran Hoyle asked. "And then just, you know, not mention that he kept talking."

Bobby Slaughter was moved in with the meth heads and the Bonfire Butcher was given his own cell for the rest of his stay.

*

It had begun typically enough. The tall man with the swagger had immediately closed in on the new arrival, who looked about as intimidating as a bunny rabbit.

"What are you in for?"

And then the Bonfire Butcher explained.

It was the explanation that did Slaughter in. He was used to bragging and no stranger to violence. He had heard (and given) many an excuse that began with the phrase, "Let me just explain," but nothing had ever quite prepared him for the Butcher's explanation.

Officer Tyrone Fuller was not concerned when he first heard the yelling. Inmates yelled. That's just what they did. They also hit and bit and spit. Not infrequently, they also pissed or puked where they weren't supposed to. It was like running a day care only with more cursing and no one was going to be picking them up at the end of the day. Hence it didn't really matter if there happened to be a little more wear and tear on them then when they'd been dropped off. So generally you just let them yell and they'd sort it out themselves. Then later you'd wander down and see what it was about and hope it was mainly hitting and biting and spitting. If it was pissing or puking, you tried not to notice and let it be the next shift's problem.

When Fuller realized it was Bobby Slaughter yelling for help, that piqued his curiosity. He walked down the hallway to the cells at a faster rate than he normally would to respond to a disturbance. That is to say it was more of a mosey than an amble. (It wasn't as if they were going anywhere and bodily excretions still had a high degree of probability.)

"I want to talk to Linden!" Slaughter was screaming by the time Fuller got there. "Tell Linden I will tell him anything he wants to know! Just get me out of here and away from this freak!"

Slaughter was literally rattling the bars. Fuller looked into the cell to assess the situation. There were, thankfully, no telltale puddles on the floor, not even blood, which was a bit surprising given the betting upstairs. The Bonfire Butcher was stretched out on the bottom bunk—which was Bobby's bunk and thus did not jibe with the apparent lack of injury to either of them.

"Bobby, seriously?" Fuller asked.

"Get me out of here!"

"You really want to lose this much cred over this guy?" He had every intention of letting him out and taking him to Detective Linden, who would be happily surprised to get a confession at this point, but not right this moment while Slaughter was freaking out and rattling his cage.

"He's going to disarticulate me in my sleep! I can't turn my back on him! He's just waiting to get his hands on my pubic tubercle!"

"He's what?" This was officially a new one.

"He's gonna slice up my pubic tubercle and disarticulate me!"

"That's not how it works," the Butcher corrected him. He squirmed on the bunk trying to find a more comfortable position and ended on his stomach trying to use his arms to cushion his head. "The pubic tubercle is just a landmark for the anterior incision. You don't actually do anything with the pubic tubercle at that point. You locate it to..."

"You don't need to be locating a man's pubic tubercle!" Slaughter shrieked indignantly. "You do not need to have your hands anywhere getting traction on a man's pubic tubercle!"

"You weren't listening," the Butcher yawned. Most people believe that the hallmark of a guilty man is nervousness. That might be true on the outside when the guilty face the stress of possible capture. On the inside, capture complete, guilty men are just tired. The Bonfire Butcher had had a long day. "The traction clamp goes at the apex of the incision," he continued, "closer to the iliac spine of the pelvis, nowhere near the pubic tubercle."

"You do not need to be getting traction on a man's pelvis! I don't care how close to the pubic tubercle you are!"

"Have you considered that you might have some issues that have nothing to do with me? You seem a little fixated on this."

Slaughter rattled the bars again. "Take me to Linden! Get me out of here! This man is crazy! He's going to disarticulate me!"

"I don't think disarticulate is a word," Fuller said.

"Of course it's a word," the Butcher snapped. "However I have already performed my quota of joint disarticulations today and I'd like to get some rest if you don't mind." He shifted again after realizing that the jailhouse budget did not include Febreze and that face-down was not a recommended sleeping position.

"Joint disarticulations?" Fuller asked. Slaughter shook his head, put his hands over his ears, and began humming "Jingle Bells".

"Disarticulation of the joint," the Butcher said. "It's fairly self-explanatory. Joints are the articulation point where two or more bones meet. You remove one of the bones and you are disarticulating it."

"You removed his bones?"

"Only...." The Butcher did some quick math. "Okay, about a quarter of his bones technically."

"I thought you hacked him up with an ax or something." Fuller wasn't allowed to watch television on duty so all his news came through the grapevine. "You popped him apart at the joints?!"

"Why does everyone think that chopping bones with an ax is less gruesome than disarticulation?"

"Dis...?" Fuller gagged. "Like twisting a drumstick off a turkey?"

"That's an unsatisfactory metaphor. Yes, twisting a drumstick off a bird would technically be disarticulation, but cooking breaks down the ligaments and fascia. You only have to break the cartilage and the meat slides right off the bone. Living tissue is interconnected in very complex..."

"Living tissue? He was alive?!" That detail hadn't made it to Fuller's end of the grapevine yet.

The Butcher looked confused by the question. "There's no reason to disarticulate a cadaver except as practice. Fairly inadequate practice really. The consistency of postmortem tissue isn't the same and you don't have to deal with bleeding. Most importantly, even with maximum sedation, the muscles of a human body can twitch and flex as you cut around them."

The next shift would have to deal with puke after all.

*

"Is he waking up? Can he be interviewed?"

"No." Dr. Cuddy flashed the young man a dirty look over her shoulder and continued to check the patient's vitals. The assistant to the Assistant District Attorney had left only to be replaced by someone that Cuddy assumed was his assistant's assistant, possibly an intern, at any rate someone very young. She couldn't get a read on whether he was enthusiastic or just nervous, but he was definitely annoying.

She did her best to ignore him and focus on the patient. She opened his eyes and shined a light in each in turn. The patient was coming around, but that wasn't a good thing given the amount of pain he would likely be in when he woke. She made some quick adjustments as she muttered, "Thank the God of Mental Illness that Wilson had enough presence of mind to place epineural catheters into the femoral and sciatic nerves before he'd started roasting marshmallows." The possibly-an-intern nodded sagely. (37.2% of all rumors start as sarcastic bullshit.)

"Wha else should I...?" House mumbled. "...pologie..."

The possibly-an-intern quickly flipped open his notebook and started frantically scribbling. Cuddy recognized the written word on the page before she processed the slurred words she was hearing. "He's apologizing?" That was an idea that got her attention. She listened more carefully.

House's voice was faint, but steady—rhythmic yet oddly monotone. "What else could I say? Everyone is gay."

More scribbling.

Cuddy had an unfortunate suspicion that she knew where this was going.

"What else could I write? I don't have the right."

She grunted. Of course an apology was too much to hope for. The scribbling continued anyway.

"What else should I be? All apologies."

Scribble. Scribble.

"You don't have to write all this down," she said.

And then the little snot shushed her. Shushed her! She was going to point out that he could just look the lyrics up online if he really thought they were important, but.... She felt old. This song was filed away in her mental filing cabinet under Recent Popular Music. She was not capable of refiling it under Oldies. She didn't care if this kid was in preschool when it was recorded.

"In the sun, in the sun I feel as one...married, buried. I wish I was like you. Easily amused."

Scribble. Scribble. Scribble.

"Well, you have fun, but I've upped his juice. You're not going to get anything useful out of him today." Cuddy made one last note on his chart and walked out.

"Find my nest of salt."

She froze halfway out the door. She realized which line was next and she wanted to hear it. Even though she knew the words were Cobain's and not his, she wanted to hear him say it.

In a flat, sleepy, but clear monotone, Gregory House said, "Everything's my fault."

"Damn straight," Cuddy agreed and left.

*

Joe Carpenter returned to the hospital grudgingly. The DA had not been amused when Carlo proudly showed off his notes of "evidence" consisting entirely of 90s rock lyrics. (A shame really, the kid had an interesting theory based on "Zombie" by The Cranberries.) So when they got word that the victim was expected to be coherent this afternoon, Carpenter was ordered to go and conduct the interview himself.

The hospital room gave Carpenter the creeps. It felt like standing inside a fish tank or worse a store window display. A dozen or more people stared in through the glass. A hospital security guard stood at the door and glared at them, but no one bothered to pretend they weren't staring nor did anyone put much effort into faking concern. Carpenter caught snatches of something ominous in whispers as he passed through the crowd into the room.

"Ma'am, Dr. Hadley?" He addressed the one doctor who'd been allowed past security. "Am I to understand there is a betting pool based on this man's recovery?"

She jerked her head slightly at an odd angle that he could not interpret as either a nod or a shake.

"Was that a yes or a no?"

There was a fraction of a second where she almost looked panicked and then the expression was gone completely and he thought he must have imagined it. "Sorry, yeah. Level of pain, presence and presentation of phantom limb, degree of freakout when he wakes. There are a lot of variables that we just don't know. All we can do is wait. And...." She shrugged. "When doctors can't do anything but wait, they...." She trailed off and gave him a tight smile.

"Why is he strapped down?" The patient's three remaining limbs were strapped with velcro restraints to the bed frame.

"That would be the unknown degree of freakout. We don't know if Wilson told him what he was doing before the...operation. No one is sure if he knows what's happened yet. And, of course, there's also the unknown level of post-operative pain."

"Why is he strapped down?" Carpenter repeated. He glanced back at the hospital guard outside the door and again had that feeling that these people didn't understand that the victim wasn't the dangerous one.

"It's like the Cone of Shame for humans," she explained.

"What?"

"You know, the plastic cone they put around a dog's neck after surgery so it can't chew on its sutures."

"You think he might accidentally injure himself as he wakes up?"

She shrugged. "It's in the betting pool, but deliberate self-injury is more heavily favored."

"Is that why there's a guard outside the door?"

She turned and looked, but she was staring at the audience outside the glass and not the guard. "That's more of a too-many-cooks thing."

"What?"

"Dr. Cuddy has taken herself off the case to avoid personal conflict. I got short straw. The guard is just to make sure that his treatment is consistent without any contradictory medication or other procedures. If another doctor were to initiate an alternate treatment without following proper protocol... Too-many-cooks."

"You need a guard to ensure professional behavior?"

"Well, the most professional and ethical physician on staff is in jail at the moment."

Carpenter glanced back at the rows of men and women in white lab coats who stood outside the glass. He shuddered.

"Why isn't he waking up? Can't you give him something to wake up faster?"

"We've been giving him sedatives to keep him from waking up for days. There's a limit to how much medication even House's body can process."

"How much longer do you think?"

"As I believe I already said, all we can do is wait for him to come around on his own." Without warning she slapped the unconscious man's face. "Oh, look, he's starting to come around."

Except he wasn't. After an initial groan and flinch, his head rolled back into the pillow. Hadley sighed and started poking his forehead.

"Should you be doing that?" Carpenter watched in horrified fascination as the poking increased to a rapid tapping. "Seriously, doesn't he have family or someone who should be here to make sure that...?" He trailed off not knowing how to end the sentence. To make sure doctors didn't slap him and place bets on his suffering?

"You mean like a medical power of attorney?" she asked. "Someone to advocate for him?"

"Yes."

"Yeah, he has one of those." She shifted her tapping to the side of his head, which, judging by his increased squirming, he apparently found more annoying. "He's in jail at the moment."

*

She told Carpenter that the problem was too many cooks in the kitchen. This was not untrue, but if that were enough then all of their patients would have guards on the door. Honestly, Hadley was confused about the situation herself. They had all been talking around the issue without really mentioning it except in hypotheticals, what-if statements that trailed off in knowing looks. The fundamental fear, what if he's worse? What if he's much, much worse? Multiple unknown variables that could combine into a myriad of possible scenarios, many of which would end...badly. House had barely tolerated his existence before. If things were worse, if the pain were worse, if the dependence on drugs were worse, and—worst of all—if his mental faculties were worse....

"Deliberate self-injury is more heavily favored," was an understatement. People were openly betting on whether House would kill himself. People were quietly whispering that he might not have to.

It wouldn't do to tell the guy from the prosecutor's office that there was a security guard on the door because Cuddy feared someone might help House to end his pain for good. Especially since Hadley wasn't sure that's what the guard was really for. Deep down, Hadley suspected the guard was there because Cuddy was a coward. The guard wasn't there to protect House. He was there to protect Chase and Foreman and Taub and maybe even Cuddy. Had Cuddy put a guard on the door and then put herself on the other side of that door to avoid "personal conflicts"—or to avoid temptation?

But why put Hadley inside that room? Hadley—who Cuddy was conveniently forgetting was not currently in possession of a valid medical license—was the one person who had demonstrably proven she was both cruel and kind enough to do what might need to be done. Of course, that also meant that Hadley—who Cuddy perhaps had not forgotten was not currently in possession of a valid medical license—was the one person who couldn't possibly risk doing it.

She hated head games. And she hated waiting. House shouldn't still be unconscious. They'd switched him to straight sedatives two days ago—at which point he'd stopped babbling—and then this morning they'd taken him off those. The sedatives were all out of his system by now, which meant he was simply asleep—or brain damaged. She had twenty dollars on brain damage herself. (Wilson should not have even attempted this shit without a trained anesthesiologist on hand.) The Greatest Hits of the 90s had been worrisome in Hadley's view because House, an amateur musician, never once hinted at a tune as he recited lyrics as if he were reading a shopping list.

They'd been artificially keeping him under to give his wounds a chance to heal before...before they had to deal with House. After the sedatives had cleared and he still slept, Cuddy gave the okay to switch off the infusion pump. The catheter would normally be removed in three to five days and it had been five already, so they were well on the safe side of medical recommendations. Completely free of sedatives, anesthesia, and analgesics, the post-operative pain alone should have woken him by now. The fact that House still slept was a bad sign or a very, very good one. Either she was about to win the pool or....

House jerked away from her poking finger and tugged at his right-hand restraint, his hand motioning to brush her away, but unable to cover the distance. As soon as he realized he was strapped down, he thrashed at all his bindings, blinking away sleep and confusion. The audience beyond the glass drew closer and tensed. This was it.

"It's all right," she reassured him. "We'll remove the restraints as soon as you're calm and coherent."

He stopped tugging at this restraints and glared at her. "What," he asked slowly, "did Wilson do?"

She fought back a grin. That didn't sound like brain damage and she could afford to lose twenty bucks.

"What do you remember of the attack?" Carpenter asked. Hadley elbowed him sharply. She had already arranged the bed flat with blankets across House's chest so that he could not see below his waist. She wanted to assess his senses before the inevitable freakout. Carpenter was not helping.

"How do you feel?" she asked.

"Who is this guy?" House asked. "What did Wilson do?"

"How do you feel?" she repeated.

"Where is Wilson?"

"James Wilson is in jail," Carpenter reassured him. "You're safe now."

"Who is this guy?"

"Doesn't matter. He was just leaving." She grabbed Carpenter and bodily shoved him out the door before he realized what was happening. "Do not let him back in," she told the guard.

"Okay, yeah," she admitted to House, "Wilson is experiencing some minor legal difficulties. It's not important. How do you feel?"

House seemed to do a personal inventory that involved tugging at each of his restraints in turn: one, two, three, pause, one, two, three, pause. House squinted at her suspiciously. "I can't move my leg."

"That's to be expected. How do you feel?"

House closed his eyes and considered. "I'm sore all over. My head hurts. My back hurts. My ass hurts."

"You've been unconscious for five days. Any symptoms that couldn't be explained by that?"

"Five days? What did Wilson do?"

"Any other symptoms?"

House stretched and then winced. "It's my hip more than my ass," he clarified. "It's not just joint pain from lying in bed for a week. Even the skin feels inflamed." He tugged at his restraints again. "Seriously, unstrap me."

"How far down the leg does the pain radiate?"

"It doesn't. You know that. You've got me completely anesthetized from the thigh down." He studied her face. "You should know that. Why don't you know that?"

"You would describe the numbness as complete then? No tingling, pricking, throbbing, itching, soreness? No pain at all?"

"What...did...Wilson...do?"

"I think Wilson just won the betting pool."

*

The DA figured he had the Bonfire Butcher case in the bag. It wasn't often a perp was nabbed literally red-handed, dripping his victim's blood, not to mention giggling—the arresting officer had written the word "giggling" on the original report, bless him—over the flaming body parts. That fateful videotaped perp walk was just icing on the cake. "Seriously? I should have done this years ago." Not so much as a flicker of remorse. The DA could get a conviction in his sleep.

The defense was equally confident for almost identical reasons. After initially cringing over that perp walk, Henderson realized he not only had a text book insanity defense, but that footage was a godsend. Once you got over the initial shock of the handcuffed man in bloodstained scrubs—and Henderson intended to make sure the jury saw the footage enough times to get over that initial shock—you saw a confused puppy dog who clearly had no idea why he was getting his nose rubbed in this mess. You couldn't look at the facts of the case without recognizing that Dr. James Wilson was completely bat-shit insane and as an added bonus he was slightly adorable. The original media reports had described him as a beady-eyed psychopath but Henderson had since seen many references in the online forums (only half of which he had typed anonymously himself) that referred to his client as "the puppy-eyed killer" and now all he had to do was remind the jury of the one fact that even the prosecution didn't dispute. The puppy-eyed killer hadn't actually killed anyone. Not-guilty by reason of insanity was a lock.

Gregory House complicated matters for both sides. From the DA's perspective, it was not helpful at all to have an abrasive unlikeable victim and he'd been forced to rule out putting the victim or any of his coworkers on the stand—which was a shame with them all being doctors. If only the victim himself could have given the expert medical testimony, the impact on the jury would have been unimaginable.

As for the defense, Henderson's main concern was that it was going to be hard to keep the jury focused on his client's obvious insanity with House likely to upstage him, racking up more crazy points at every turn. Henderson kept House's name on the potential witness list, but hoped never to call him to the stand. Pointing out that the victim was a total prick was potentially effective but not a move that Henderson really wanted on his resume.

Nonetheless, Greg House had swung into court without warning on the first day of jury selection. Henderson wasn't quite sure what you called that form of locomotion on crutches, but House used the same method as a twelve-year-old boy who had stolen a pair of crutches he didn't need, swinging needlessly fast and at times almost violently, overtaking mere bipeds in the blink of an eye. (When standing still, he also favored the same method of twelve-year-old boys on stolen crutches, that of attempting to balance without touching the ground.) House had swung himself all the way down the aisle before anyone realized he was even there. He let his crutches fall to the ground as he vaulted the railing and launched himself at the defendant. The room collectively gasped. The bailiffs ran forward to break up the...attack, but there was no attack to break up. There in the front of the courtroom in full view of the entire prospective juror pool and as many reporters as could squeeze themselves into the back, the Butcher's victim planted a sloppy squelchy kiss on the accused.

When he was let up for air, Wilson calmly asked, "Feeling better?"

"Better?" House purred. "Better is an utterly inadequate word."

"You'll slap me if I say I told you so, won't you?" Wilson asked.

"You told me so?" House spluttered. "You told me? How about I told you so? Huh? You've been telling me for years that my pain was all in my head. That I was exaggerating if not inventing it entirely. That I was being unreasonable. That I had no right to still be angry. Well, it was real. This proves it was real. All this time the pain was real and so intense that even I didn't realize how much of that background buzz of hatred was pure pain."

"If you'd just followed the doctor's recommendation in the first place..." Wilson trailed off under House's glare. "You're a stubborn bastard. That's all I'm saying. You're a stubborn bastard and you make things harder on yourself than they need to be. But," Wilson hesitated, "it's all over now?"

House shrugged. In full fucking view of the entire prospective juror pool, House shrugged. The District Attorney was not a happy person.

"I was about to say, 'No blood, no foul,'" House smirked, "but apparently you were messy."

Wilson nodded in agreement. "I didn't tie off the distal sutures thoroughly enough. It seemed like a waste of time when I needed to finish as quickly as possible so I could call the ambulance. When I threw your leg over my shoulder to carry it out, it kind of went splat."

"Why did you set fire to it?"

"Because you're a stubborn bastard. I had these horrible visions of you demanding that they sew it back on."

House cocked his head to one side apparently considering the logistics of the idea. "Fire was a good plan," he finally agreed. "Okay, we're even."

"The defense moves for a mistrial!" Henderson was beaming.

"The trial hasn't even started yet," Judge Alvarez said.

Henderson didn't trust himself not to giggle so he just nodded enthusiastically.

"Does the prosecution have an opinion on this?" Alvarez asked waving his gavel hopefully.

The DA glowered at the defendant's table for a moment. Even if they continued, they'd have to dismiss this batch of jurors and he was planning to retire at the end of this term so to hell with the reporters as well. "Oh, just get them out of my sight before I set fire to both of them myself. The prosecution moves for dismissal."

"Case dismissed! Court adjourned!"

*

Lisa Cuddy would never forgive Greg House for costing her the best oncologist that Princeton-Plainsboro Teaching Hospital had ever had. The criminal justice system had opted to write the incident off as an unorthodox back alley medical procedure. Wilson had reimbursed the hotel for all the damage (blood stains and associated cleaning fees). And three different publishers engaged in a bidding war for the Bonfire Butcher's memoirs. The medical board was not as amused and as a result neither House nor Wilson ever set foot inside Princeton-Plainsboro again.

Foreman and Chase had both sulked when she'd hired from outside rather than promote either of them. "You are all tainted," she had told them. "Contaminated. Suspect. I will never trust any of you. Give me one reason, one tiny reason, to fire you and you're gone. You were trained by a lunatic and you do not get to run the asylum." They couldn't argue with that.

Dr. Victoria Johnson was a deceptively frail-looking old woman with Einstein hair and a penchant for turtlenecks and large costume jewelry. She brooked no shenanigans on her watch. For the most part, no shenanigans occurred that she found out about. (And she hadn't even gotten terribly upset about the ball python. She'd just called animal control and gone on with the case at hand.)

Taub was up to his third or fourth midlife crisis and was mainly confused that life hadn't gotten noticeably easier with House gone—a tad more predictable perhaps, but not easier.

No one really knew what happened to House and Wilson after they left, but Chase told Foreman that before Wilson's trial had fallen apart House had solved both a murder and a jewel theft just because he'd been hovering around the police snooping where he didn't belong. Utilizing some contacts of Cuddy's ex-boyfriend, House had gotten a private eye license and he and Wilson were now solving crimes a la Nero Wolf and Archie. (Chase had told Taub that House was in the Italian Alps training with a paralympic skiing team and that he'd patented his own design for an improved ski pole. Chase was full of shit.)

Abbot in radiology found a photo online that looked a lot like House. It was a fluff piece in a Florida newspaper. The photo was of a man with a full beard and a grubby captain's hat and the article identified him as a boat captain who'd gotten his right leg torn off by a tiger shark, but who still fearlessly went out scuba diving almost every day. The background was out of focus and she was cut off at the edge of the frame so Foreman was never sure, but there was a woman in the background who looked a lot like Remy. Even years from now he would sometimes catch himself looking at that photo and wondering.

Remy Hadley resigned two months ago. She could still pass for normal—on a good day, if you didn't look too hard. But she had started dropping things more often. She tossed her hair out of the way with a sharp jerk—even when her hair wasn't in the way. She recognized before anyone else did that she couldn't be trusted with a hypodermic or a scalpel. Foreman had pointed out that she could delegate most of those hands-on tasks, but she'd only glared at him and then one day she was just gone.

He liked to imagine the three of them were out there on a boat in the Gulf of Mexico bullshitting tourists with tales of shark attacks and lost treasure in exchange for beer money. And, what the hell, sometimes he liked to imagine they really had formed a floating detective agency, solving crimes along the Redneck Riviera. And when Remy couldn't pass for normal even on a good day, when the Danse Macabre finally took control, House and Wilson together would be cruel enough and kind enough to do what needed done.

Foreman overheard two young nursing students gossiping about the first anniversary of the Bonfire Butcher and just like that a year had passed. Foreman still got annoyed that the story was always told wrong. Wilson was always the beady-eyed psychopath and House the innocent victim. For the first few months, those who knew better would try to put the story straight. But it had a life of its own now. If it hadn't been a slow news day—if only a school bus had spilled little children across the asphalt or a tornado had taken out a strip mall or a hot celebrity had overdosed—if a bored editor had never been compelled to alliteration and birthed the Bonfire Butcher, if there had never been a bloodstained perp walk, then the truth might have had a chance. The legend won. The Bonfire Butcher was born and the Bonfire Butcher would never die.

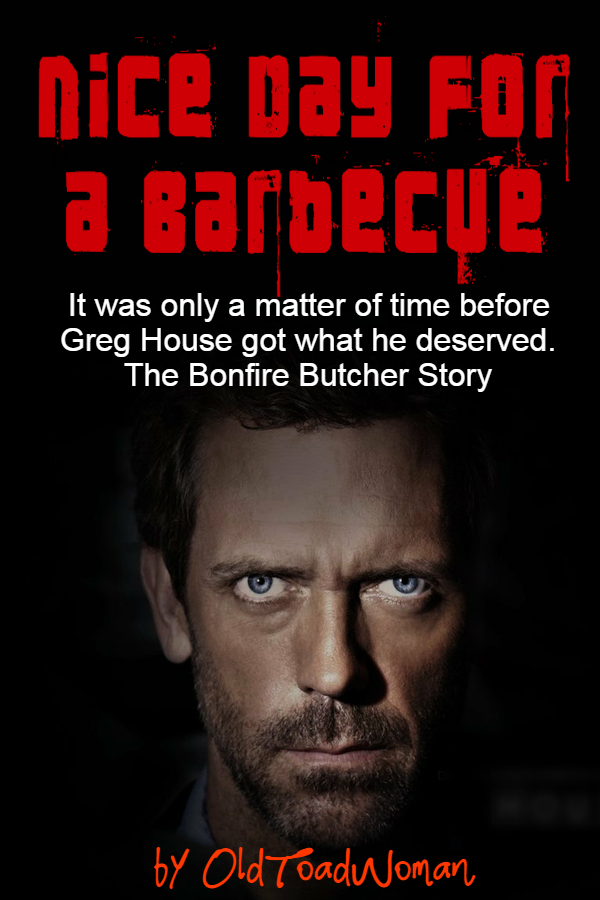

That night, one year to the day, Tom Jenks had the first of many nightmares about the beady-eyed man with the bloodstained face who smiled shyly through the smoke as he said, "Nice day for a barbecue."